James Webb Space Telescope Discovery

Clicking on each image will open the full resolution one. Try it!Clicking on "Raw images" image will yield all the relevant raw images.

No tricks, just treats

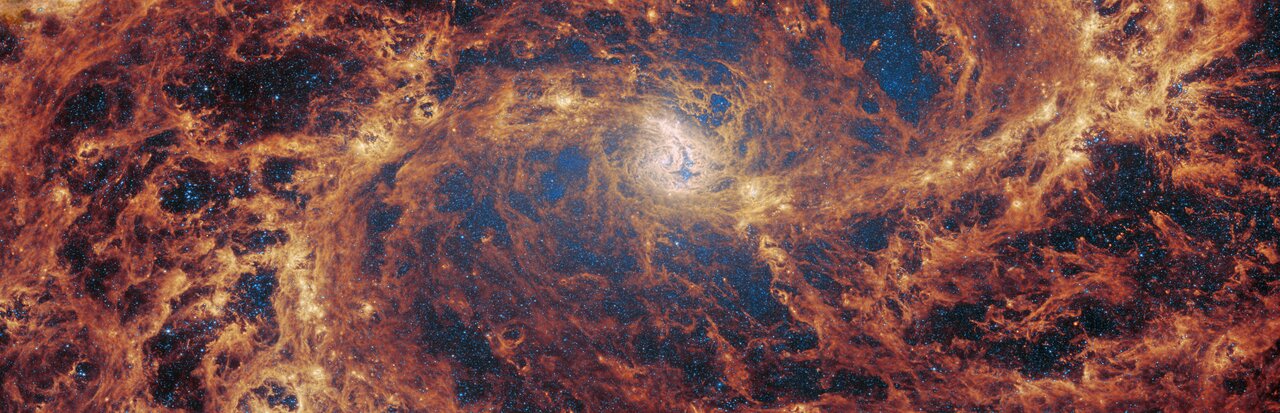

This month, Webb presents a spectacular treat… for the eyes. The barred spiral galaxy M83 is revealed in detail by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope. M83, which is also known as NGC 5236, was observed by Webb as part of a series of observations collectively titled Feedback in Emerging extrAgalactic Star clusTers, or FEAST. Another target of the FEAST observations, M51, was the subject of a previous Webb Picture of the Month. As with all six galaxies that comprise the FEAST sample, M83 and M51 were observed with both NIRCam and MIRI, two of the four instruments that are mounted on Webb.

MIRI, or the Mid-InfraRed Instrument, makes observations in the mid-infrared, which spans wavelengths of light very different from optical wavelengths. Optical wavelengths in astronomy roughly correspond to the range of light waves that human eyes are sensitive to, and extend from about 0.38 to 0.75 micrometres (a micrometre, or micron, is one thousandth of a millimetre). By contrast, MIRI detects light from 5 to 28 micrometres — however, when it makes observations, it does not typically observe across this entire wavelength range all at once. Instead, MIRI has a set of ten filters that allow very specific regions of light through. For example, one of MIRI’s filters (dubbed F770W), allows light with wavelengths of 6.581 to 8.687 micrometres to pass through it.

This image was compiled using data collected through just two of MIRI’s ten filters, near the short end of the instrument’s wavelength range. The result is this extraordinarily detailed image, with its creeping tendrils of gas, dust and stars. In this image, the bright blue shows the distribution of stars across the central part of the galaxy. The bright yellow regions that weave through the spiral arms indicate concentrations of active stellar nurseries, where new stars are forming. The orange-red areas indicate the distribution of a type of carbon-based compound known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (or PAHs) — the F770W filter, one of the two used here, is particularly suited to imaging these important molecules.

Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, A. Adamo (Stockholm University) and the FEAST JWST team

MIRI image: full image, low res

MIRI image: full image, low res

MIRI image: partial image, high res

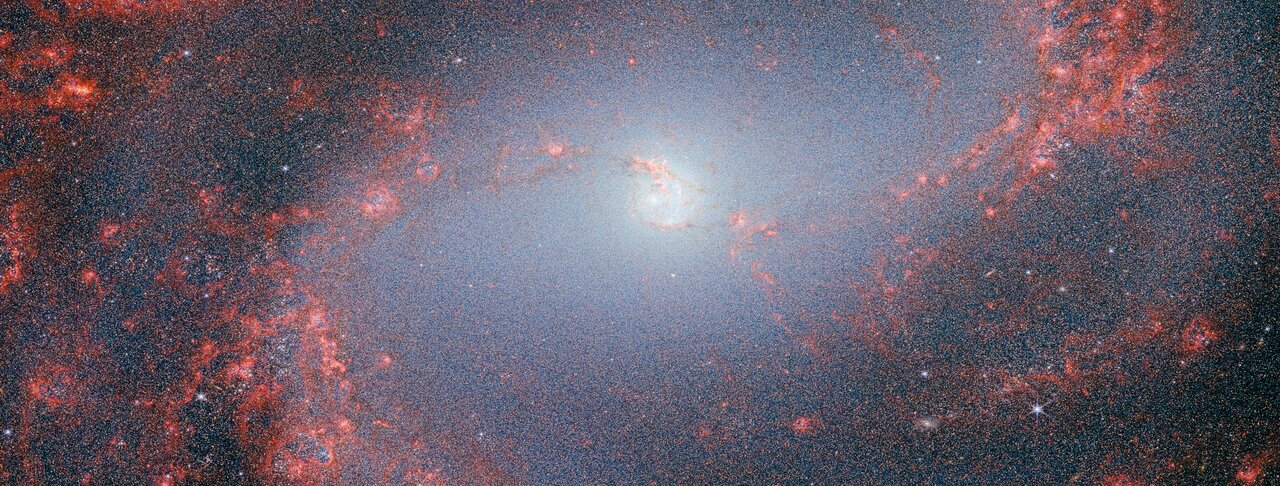

This image was captured by Webb’s NIRCam, or Near-InfraRed Camera. NIRCam makes observations in the near-infrared, which spans wavelengths of light that are just longer than optical wavelengths. Like MIRI, it is equipped with a range of filters that cover its wavelength range of 0.6 to 5 micrometres, including 29 filters specifically intended for imaging. Data collected through eight of those filters were used to complete this impressive image, which picks out light emitted from the wealth of stars that might be obscured by dust at other wavelengths. Even though stars do not emit the majority of their light in the infrared, optical light is much more vulnerable to being scattered by dust than infrared light is, and so infrared instruments like Webb can provide the best opportunities to study stars in regions (like galaxies) that might also contain large amounts of dust.

In this image, the bright red-pink spots correspond to regions rich in ionised hydrogen, which is due to the presence of newly formed stars. The diffuse gradient of blue light around the central region shows the distribution of older stars. The compact light blue regions within the red, ionised gas, mostly concentrated in the spiral arms, show the distribution of young star clusters.

MIRI image: partial image, high res

This image was captured by Webb’s NIRCam, or Near-InfraRed Camera. NIRCam makes observations in the near-infrared, which spans wavelengths of light that are just longer than optical wavelengths. Like MIRI, it is equipped with a range of filters that cover its wavelength range of 0.6 to 5 micrometres, including 29 filters specifically intended for imaging. Data collected through eight of those filters were used to complete this impressive image, which picks out light emitted from the wealth of stars that might be obscured by dust at other wavelengths. Even though stars do not emit the majority of their light in the infrared, optical light is much more vulnerable to being scattered by dust than infrared light is, and so infrared instruments like Webb can provide the best opportunities to study stars in regions (like galaxies) that might also contain large amounts of dust.

In this image, the bright red-pink spots correspond to regions rich in ionised hydrogen, which is due to the presence of newly formed stars. The diffuse gradient of blue light around the central region shows the distribution of older stars. The compact light blue regions within the red, ionised gas, mostly concentrated in the spiral arms, show the distribution of young star clusters.

NIRCam image

NIRCam image

Raw images (note: the raw images belong to another proposal)

Raw images (note: the raw images belong to another proposal)