James Webb Space Telescope Discovery

Clicking on each image will open the full resolution one. Try it!Clicking on "Raw images" image will yield all the relevant raw images.

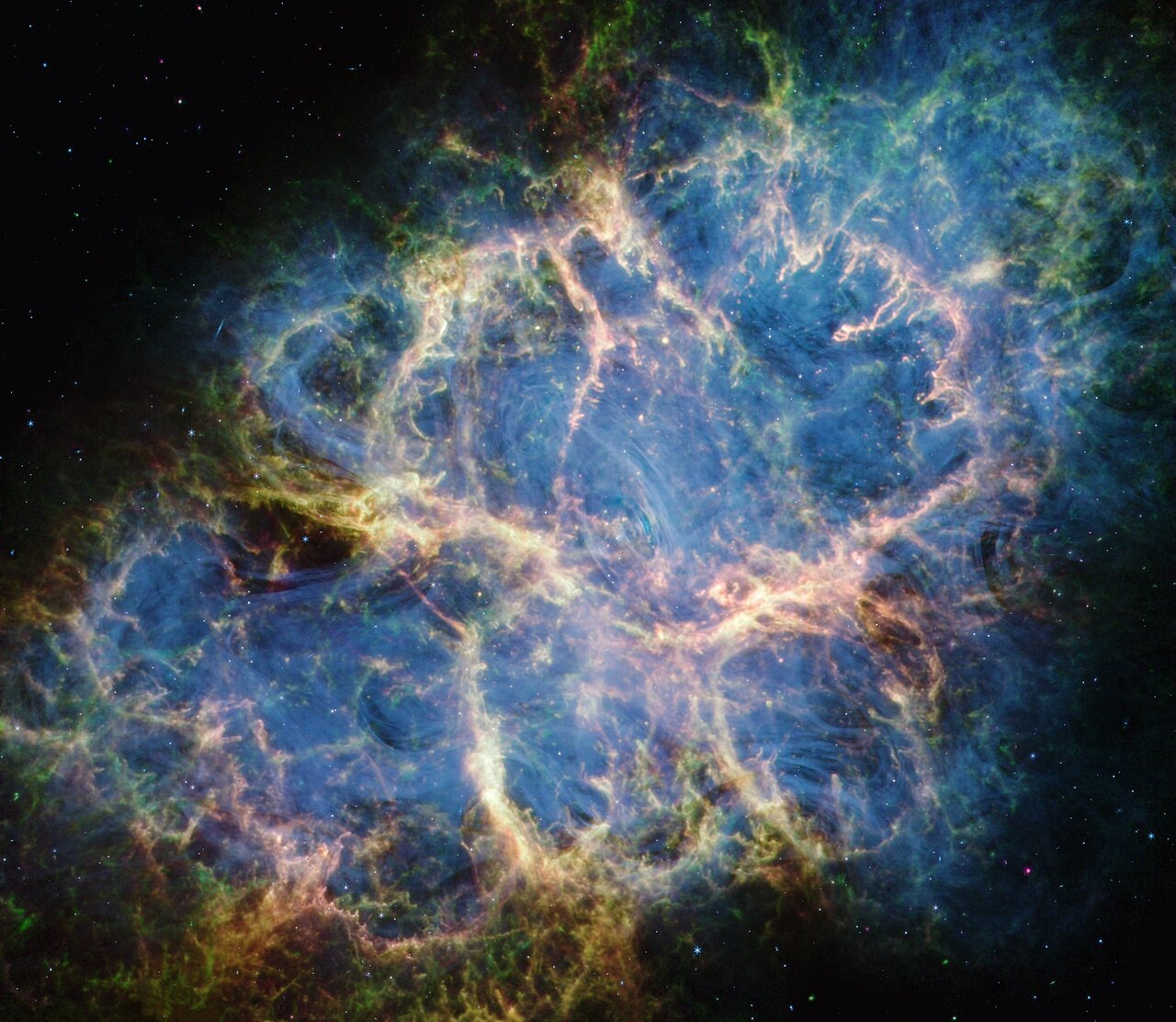

Crab Nebula (MIRI and NIRCam image)

The Crab Nebula is a nearby example of the debris left behind when a star undergoes a violent death in a supernova explosion. However, despite decades of study, this supernova remnant continues to maintain a degree of mystery: what type of star was responsible for the creation of the Crab Nebula, and what was the nature of the explosion? The NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope has provided a new view of the Crab, including the highest-quality infrared data yet available to aid scientists as they explore the detailed structure and chemical composition of the remnant. These clues are helping to unravel the unusual way that the star exploded about 1000 years ago.

A team of scientists used the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope to parse the composition of the Crab Nebula, a supernova remnant located 6500 light-years away in the constellation Taurus. With the telescope’s MIRI (Mid-Infared Instrument) and NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera), the team gathered data that are helping to clarify the Crab Nebula’s history.

The Crab Nebula is the result of a core-collapse supernova that was the death of a massive star. The supernova explosion itself was seen on Earth in 1054 CE and was bright enough to view during the daytime. The much fainter remnant observed today is an expanding shell of gas and dust, and an outflowing wind powered by a pulsar, a rapidly spinning and highly magnetised neutron star.

The Crab Nebula is also highly unusual. Its atypical composition and very low explosion energy have previously led astronomers to think it was an electron-capture supernova — a rare type of explosion that arises from a star with a less-evolved core made of oxygen, neon, and magnesium, rather than a more typical iron core.

Past research efforts have calculated the total kinetic energy of the explosion based on the quantity and velocities of the present-day ejecta. Astronomers deduced that the nature of the explosion was one of relatively low energy (less than one-tenth that of a normal supernova), and the progenitor star’s mass was in the range of eight to 10 solar masses — teetering on the thin line between stars that experience a violent supernova death and those that do not.

However, inconsistencies exist between the electron-capture supernova theory and observations of the Crab, particularly the observed rapid motion of the pulsar. In recent years, astronomers have also improved their understanding of iron-core-collapse supernovae and now think that this type can also produce low-energy explosions, providing the stellar mass is adequately low.

To lower the level of uncertainty about the Crab’s progenitor star and the nature of the explosion, the science team used Webb’s spectroscopic capabilities to home in on two areas located within the Crab’s inner filaments.

Theories predict that because of the different chemical composition of the core in an electron-capture supernova, the nickel to iron (Ni/Fe) abundance ratio should be much higher than the ratio measured in our Sun (which contains these elements from previous generations of stars). Studies in the late 1980s and early 1990s measured the Ni/Fe ratio within the Crab using optical and near-infrared data and noted a high Ni/Fe abundance ratio that seemed to favour the electron-capture supernova scenario.

The Webb telescope, with its sensitive infrared capabilities, is now advancing Crab Nebula research. The team used MIRI’s spectroscopic abilities to measure the nickel and iron emission lines, resulting in a more reliable estimate of the Ni/Fe abundance ratio. They found that the ratio was still elevated compared to the Sun, but only modestly so and much lower in comparison to earlier estimates.

The revised values are consistent with electron-capture, but do not rule out an iron-core-collapse explosion from a similarly low-mass star. (Higher-energy explosions from higher-mass stars are expected to produce Ni/Fe ratios closer to solar abundances.) Further observational and theoretical work will be needed to distinguish between these two possibilities.

Besides pulling spectral data from two small regions of the Crab Nebula’s interior to measure the abundance ratio, the telescope also observed the remnant’s broader environment to understand details of the synchrotron emission and the dust distribution.

The images and data collected by MIRI enabled the team to isolate the dust emission within the Crab and map it in high resolution for the first time. By mapping the warm dust emission with Webb, and even combining it with the Herschel Space Observatory’s data on cooler dust grains, the team created a well-rounded picture of the dust distribution: the outermost filaments contain relatively warmer dust, while cooler grains are prevalent near the centre.

Credit: ESA

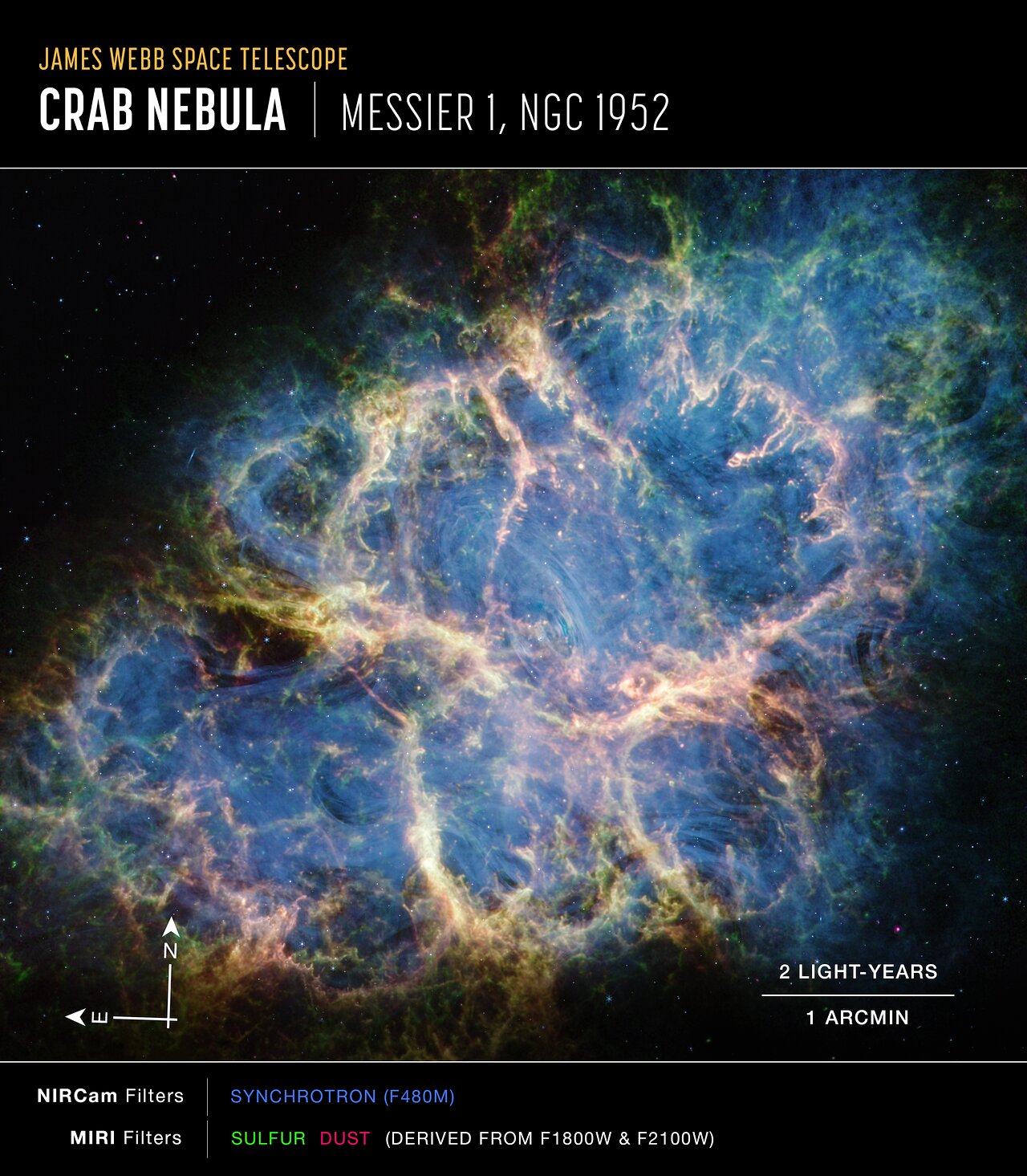

The NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope dissected the Crab Nebula’s structure, aiding astronomers as they continue to evaluate leading theories about the supernova remnant’s origins. With the data collected by Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument), a team of scientists were able to closely inspect some of the Crab Nebula’s major components.

For the first time ever, astronomers mapped the warm dust emission throughout this supernova remnant. Represented here as fluffy magenta material, the dust grains form a cage-like structure that is most apparent toward the lower left and upper right portions of the remnant. Filaments of dust are also threaded throughout the Crab’s interior and sometimes coincide with regions of doubly ionised sulphur (sulphur III), coloured in green. Yellow-white mottled filaments, which form large loop-like structures around the supernova remnant’s centre, represent areas where dust and doubly ionised sulphur overlap.

The dust’s cage-like structure helps constrain some, but not all of the ghostly synchrotron emission represented in blue. The emission resembles wisps of smoke, most notable toward the Crab’s centre. The thin blue ribbons follow the magnetic field lines created by the Crab’s pulsar heart — a rapidly rotating neutron star.

Credit:

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, T. Temim (Princeton University)

The NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope dissected the Crab Nebula’s structure, aiding astronomers as they continue to evaluate leading theories about the supernova remnant’s origins. With the data collected by Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument), a team of scientists were able to closely inspect some of the Crab Nebula’s major components.

For the first time ever, astronomers mapped the warm dust emission throughout this supernova remnant. Represented here as fluffy magenta material, the dust grains form a cage-like structure that is most apparent toward the lower left and upper right portions of the remnant. Filaments of dust are also threaded throughout the Crab’s interior and sometimes coincide with regions of doubly ionised sulphur (sulphur III), coloured in green. Yellow-white mottled filaments, which form large loop-like structures around the supernova remnant’s centre, represent areas where dust and doubly ionised sulphur overlap.

The dust’s cage-like structure helps constrain some, but not all of the ghostly synchrotron emission represented in blue. The emission resembles wisps of smoke, most notable toward the Crab’s centre. The thin blue ribbons follow the magnetic field lines created by the Crab’s pulsar heart — a rapidly rotating neutron star.

Credit:

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, T. Temim (Princeton University)

Crab Nebula (MIRI and NIRCam image, annotated)

Crab Nebula (MIRI and NIRCam image, annotated)