James Webb Space Telescope Discovery

Clicking on each image will open the full resolution one. Try it!Clicking on "Raw images" image will yield all the relevant raw images.

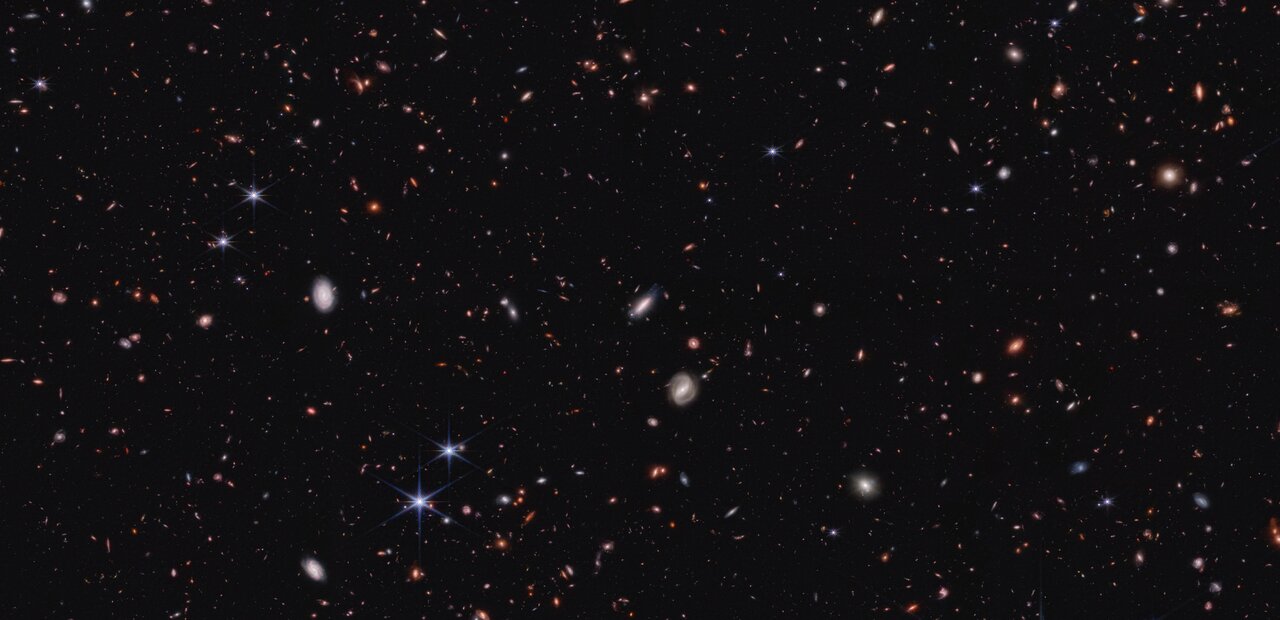

CEERS crop (NIRCam image)

When astronomers got their first glimpses of galaxies in the early Universe from the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, they were expecting to find galactic pipsqueaks, but instead they found what appeared to be a bevy of Olympic bodybuilders. Some galaxies appeared to have grown so massive, so quickly, that simulations couldn’t account for them. Some researchers suggested this meant that something might be wrong with the theory that explains what the Universe is made of and how it has evolved since the big bang, known as the standard model of cosmology.

According to a new study in the Astrophysical Journal, some of those early galaxies are in fact much less massive than they first appeared. Black holes in some of these galaxies make them appear much brighter and bigger than they really are. The evidence was provided by Webb’s Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) Survey.

According to this latest study, the galaxies that appeared overly massive likely host black holes rapidly consuming gas. Friction in the fast-moving gas emits heat and light, making these galaxies much brighter than they would be if that light emanated just from stars. This extra light can make it appear that the galaxies contain many more stars, and hence are more massive, than we would otherwise estimate. When scientists remove these galaxies, dubbed “little red dots” (based on their red color and small size), from the analysis, the remaining early galaxies are not too massive to fit within predictions of the standard model.

However, there are still roughly twice as many massive galaxies in Webb’s data of the early Universe than expected from the standard model. One possible reason might be that stars formed more quickly in the early Universe than they do today. Star formation happens when hot gas cools enough to succumb to gravity and condense into one or more stars. But as the gas contracts, it heats up, generating outward pressure. In our region of the Universe, the balance of these opposing forces tends to make the star formation process very slow. But perhaps, according to some theories, because the early Universe was denser than today, it was harder to blow gas out during star formation, allowing the process to go faster.

Credit: ESA, NASA, CSA, STScI

CEERS crop (NIRCam image)

CEERS crop (NIRCam image)